There’s more to Mexico than Tequila

By Sam Bygrave

Tequila rightly gets a lot of the international limelight. But there was a time when the image of Tequila was one of terrible hangovers and poor quality. Until recently, mezcal (of which Tequila is a member – all Tequilas are mezcals but not all mezcals are tequila) had much the same reputation – it was the spirit that had the worm in the bottle and people didn’t know much more about it. Indeed, the great boozer, Sir Kingsley Amis, once wrote: “I think the nastiest drink I’ve ever drunk in my life was some stuff called mezcal in a Mexican market town.” But that has all changed.

Within Mexico there was that view as well. But there are also other spirits native to Mexico that are now escaping a previous reputation for being moonshines of nefarious quality. Looking at the state from which they come is a good key to expoloring them further.

But why do they want this appellation status in the first place? Denomination of origin status helps producers to raise the quality and establish a brand for their products, muh in the way that Bordeaux and Burgundy wines have established their reputation. It is a way of ensuring that the rising tide floats all ships. There are strong economic imperatives behind the move to denomination of origin status.

Tequila

The two great geographical distinctions in the production of tequila in Jalisco is that between those produced in the highlands (which results in agaves that are sweeter and larger, because they receive more sunlight and can ripen longer) and those in the lowlands (where the agaves are more herbaceous and smaller). Tequila from the lowlands valley – Tequila Partida is one example – is often a little spicier and earthier; those from Los Altos (like Excellia and Patron) tend to be more delicate and floral.

Tequila can also be produced in other states: Guanajuato, Michoacán, Nayarit and Tamaulipas, though something like 99% of tequila comes from Jalisco.

Mezcal

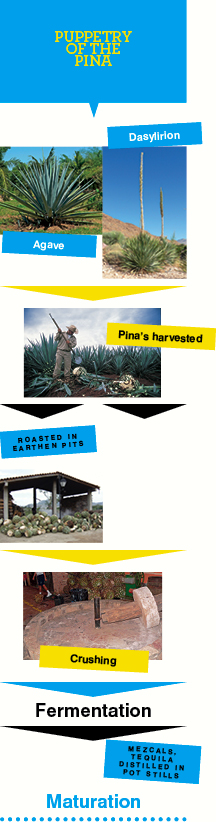

Mezcal is produced in a number of Mexican states, chief among them Oaxaca, but also in Durango, Guerrero, Oaxaca, San Luis Potosi, Zacatecas, Guanajuato and Tamaulipas. Espadin is the variety of agave most often used, but there are 30 different varieties allowed to be used under the mezcal denomination. Although there are large-scale, commercial mezcals available, most of the mezcals that are making waves are smaller brands, often the product of single villages and made in much the same manner as they have been for hundreds of years. They are often pot still products, and the pinas are roasted in pits with fires fuelled by wood and mesquite (which is where the note in most mezcals is derived).

Ever seen a bottle of mezcal with the word pechuga or conejo on the label? These mezcals will have various fruits and nuts thrown in to the distillation, and in the case of pechuga poultry breast – sometimes chicken, sometimes turkey – is suspended in the still, contributing a meaty flavour that balances out the fruit.

Bacanora

In certain municipalities in Sonora, the agave Yaquiano (also known as the agave Pacifica) is used to create a mezcal by the name of Bacanora (after one of the principal towns of production). The agave grows in the mountains, and was granted deonomination of origin status.

So what the hell is Sotol?

Sotol is very similar in many respects to mezcal but is made but from a plant called the Desert Spoon, or Dasilyron. The plant grows throughout the norther deserts of Mexico (and can be found in Texas) and has long been the preferred drink of the people who live there. It is know in Mexico for being akin to moonshine, but quality has improved and sotol is beginning to be seen more in the US and here in Australia. It is similar to mezcal in taste, but with more herbaceoiusness.