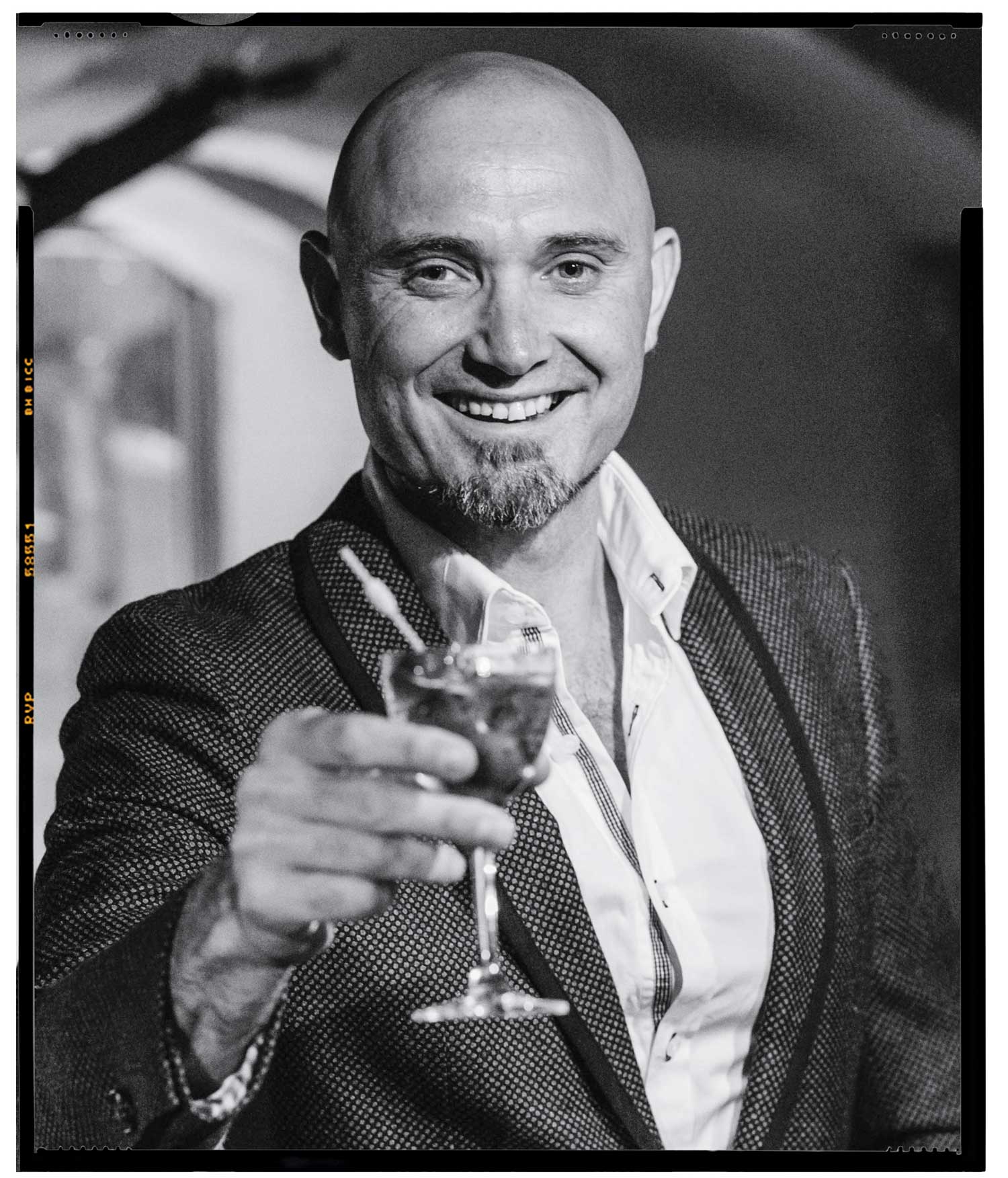

SVEN ALMENNING is the managing director and owner of the influential Speakeasy Group of venues — Eau de Vie Sydney and Melbourne, Boilermaker House, Mjølner Sydney and Melbourne, and the forthcoming Parramatta venue, Nick & Nora’s.

It’s fair to say that Almenning is a busy guy, who has only got busier having launched Ananas, a training and management platform for the hospitality industry.

Here, lightly edited for length and clarity, he talks to Sam Bygrave about his journey through the bar life.

As told to Sam Bygrave

I did a bar course in LA… I think it was three weeks — it was full on, eight hours a day. And I thought that was great, [but] I never thought it would be something I’d stick to. It was full on. But you got a job placement afterwards.

It was just so I could work bars while travelling. It wasn’t until I moved here in 1999 and I got a job at The Basement [in Sydney] that I got into it. And then Dave Champ, who used to head up Merivale, recruited me and poached me from The Basement.

I started to learn that there was more to bartending than just slinging shots and picking up girls — which of course was a the bonus at the beginning — but once I discovered there was more to it I started to get into it. And I think that after I started learning about the history of spirits, that’s when I got hooked. So probably about 2001 I started realising this was something I was keen on doing.

By the time I set up Behind Bars it was 2006, so I’d been in Australia bartending for seven years, bartended on and off for a decade. And I’d worked for Dave [Spanton] at Bartender Magazine as a senior writer for a year, before I set up Behind Bars, and that really helped.

I think setting up a company, you don’t need a business degree — you just really need to want to make it work.

Behind Bars started off with me working on it part time whilst tending bar. My wife, Amber, went full time on it before I did. She would do training sessions and travel around and all that. We ran it out of our spare bedroom in Rose Bay, and then towards the end, I think we had 25 full time staff, [and] we had between 70 and 100 consultants or casual employee who’d come and do cocktail sessions or training sessions or run events, and we probably turned over three and half million a year — it was a good little business. At the time I think we were maybe the biggest industry consultancy company in the world for bars, I didn’t hear of anyone who operated at the scale that we did. We did 100 events a year, we created the World Class program, we created the Ketel One Fraternity, we ran the Alchemy program — it was a lot of fun. It was good. And it obviously helped us get to a place where we could start opening bars.

Eau de Vie to me is like… you know The Flight of the Conchords? Their first season? That shit had been in the works for a while — they knew what that was going to be. Like an artist who comes up with their first album, that’s been worked on for five or 10 years and then they’ve got to do the next one in 12 months. That was Eau de Vie for us: we had the concept ready, we’d been working on it, we had written all this down, and it had been in my mind for years. Once we found the right venue, we were lucky enough to be able to afford to take it.

I think the work is fine, it’s the risk that is hard. I mean, remortgaging your house at my age sucks. And we just did that for Nick & Nora’s. I think people don’t necessarily understand the risk that goes into it, when you open a venue you put pretty much everything you own on the line before you have anyone in the door. I think the reason we do it is that, [business partner] Greg [Sanderson] and I get really caught up in our concept, in an idea, and we want to do it. And a lot of the things we want to do — and we’re having a talk at Bar Week about how we ignored good business advice — a lot of them are, on paper, really dumb ideas and we kind of just want to prove that it can work. We just really want to open venues we think are going to be great. I don’t think that’s ever going to go away.

And that’s kind of what drives it — we don’t really have a money goal or a turnover objective or an valuation objective or an exit plan; we just want to open fun, cool, interesting venues that deliver weird and wonderful experiences. That’s the plan — it’s not even a plan, it’s just kind of what happens!

I think it’s very unhealthy to have a big ego. I think that if you have a big ego, and you think that you know the best— I got it from an old, old quote from Bill Gates. He said, ‘Surround yourself with people who are better than you.’ And then I read this other quote from Mark Zuckerberg, and it was amazing, he goes, ‘If you’re hiring someone, especially if you’re hiring a manager, you have to ask yourself: in an alternative universe, if things were different, would I work for this person?’ I think it’s a really good question because if I’m not going to work for them, why would I ask other people to work for that person?

I find that if you think you know everything best — well, you’re just arrogant to start with — but also you’re holding back your potential, and you’re not going to have people around for a long time. I want to hire the best people in the business, and then I want to trust them to do the right job. I think there are things in our business that I do better than others, and I will fight for my opinion a bit more, and I’ll need to be convinced by them that I’m wrong. I am convinced of that on a daily basis! But also if you’re going to keep staff around for a while, they need to be able to do things that they believe are correct, and if they’re constantly doing things in the venue that they disagree with, they’re probably not going to do it to start with, and so your policies aren’t going to be implemented anyway.

I don’t think you need to think you can do things better than others, I think you need to think that you can do what you want to do well. One of the issues I have with say, awards, is that we aren’t comparing apples with apples, and to call one thing out as being better than another, can be a bit farfetched.

That’s why most of us like to celebrate that we’re in the final four or final five or final ten, because that’s great. But to be heralded as better than others, that’s difficult. I have a very strong views on what’s great and what’s not great, but I think you should believe that I can do what I want to do really fucking well. And I think it’s important to be different. What was happening with bars in Australia 20 years ago was that we were all the same — everybody had the same beers, the same wines, the same sprits, the same cocktails, you know? The idea was we were going to be doing what everybody else does, at the same level. And now it’s mostly about how can I do my niche, really fucking well. How am I going to get people come to my place, instead of somewhere else. Not necessarily because we’re better, but because we offer a different experience. And I would say that Mjolner offers a different experience to any other restaurant, right? But I wouldn’t say it’s better than any other restaurant. It’s different and good and therefore you should come and try that, as opposed to going, ‘Fuck it, we shit on everybody else.’

I love training. Part of it’s practical, and part of it’s philosophical, so I might start with the philosophical first. The most rewarding piece of when we did the Alchemy training was we watched the industry change. So we watched it go from being largely untrained — we trained 15,000 people a year. A big part of that is publications like Bartender magazine, which has been driving education way before we did any training. But when we started doing the training a lot of other companies did the same as well. So we did 15,000 a year, but then you had all the other companies train as well. So we saw basic things like how you make a mixed drink, that changed. We watched the industry change. One thing that’s been frustrating me is that we don’t really have a career path for bar and wait staff. For chefs there is a path: you can do this training and that training, you get a piece of paper and you can prove that you know something. And I find that we’re hiring people, and my thinking has been for years that if there was an almost an industry approved path, for bar staff, for waitstaff, the minimum bits you should know or prove that you know, we could use that in how we pay our staff, calculate wages, how we hire people. I want to be that benchmark that people need to have at least this [minimum of] knowledge and at least these skills in order to get a job. I want our industry to be perceived as a professional industry, I don’t want people to think that it’s unskilled. You know, Tim Phillips is not fucking unskilled. That guy is amazing. Jack Sotti — amazing. Nathan Beasley — amazing. These guys know so much. But when you tell people you work in the bar industry, people think it’s completely unskilled — I want to change that perception. And I think you have to start with training.

The more practical reason is, trying to run our group with 130 staff is difficult without some kind of software that allows me to see who cares, who puts in the effort, who’s doing training, who knows what. If I’m going to open up a new whisky bar, with Ananas, I can simply go into the platform and type in whisky, and rank all the staff in my group based on who’s got the most whisky knowledge. I can find that in 10 seconds, who the top five on whisky are, and I can go talk to them about my ideas. If I want to open up a wine bar I can do the same. If all of a sudden, someone leaves Mjolner who has a lot of wine knowledge, I can go into Ananas, type in wine and rank my people.

We built it to facilitate that management of staff.

One of the things you can do, when you invite staff to your business you give them a job role — this person is a bartender, this person’s a waitperson, this person’s an admin — whatever. When you do your internal training, you allocate each course based upon their position. You send them an invitation, and the second they accept it, they have access to all the internal training for your venue that applies to his or her position.

I have a few standout experiences when it comes to bartenders. Tim Phillips? Fucking outstanding. I remember him working at Black Pearl, he was serving me and Amber and giving us VIP treatment, whilst stitching up Rob Sloan at the same time by getting some girls to pretend they’d seen him in Cosmo and he’d won hottest bartender or whatever it was, while serving other people at the bar, and cracking jokes — how can you do all of this at once? It was just a wonderful thing to watch. Zdenek Kastanek, I remember he was working at The Lincoln, he was so amazing behind the bar I ran home, and woke up my wife who was sleeping and asked her to get out of bed and come with me to The Lincoln to watch this guy bartend. She was like, ‘You gotta be kidding me.’ I went back and kept watching him bartend, he was beautiful, the flow behind the bar — he’s amazing behind the bar.

I like hiring great people because I believe that if I hire the right people they will teach me something, or will teach our staff something, something that doesn’t come from my playbook. Our approach generally is if we can hire someone who is fantastic, we will hire that person because they will broaden our horizons. I don’t think that just hiring green people saying ‘Well I know best, I can teach you everything,’ — that’s okay for a portion of your staff. But I have a feeling that your business isn’t going to prosper in the same way as if you have put people in that know more.

Eau de Vie wasn’t me — it was Barry [Chalmers] who was the one. Then you had Luke Redington, you had fucking Max Greco — Max Greco probably taught me more about customer service in a night than 20 years hospitality did before. There’s not a day I don’t miss Max — he’s just incredible. All these people teach you things that you’re missing, and when they leave, it’s hard — you think how am I ever going to fill those shoes? You try — I mean you can never fill Max’s shoes, they’re just un-fillable —but I think one thing we’re really proud of is being able to attract these people to our business. And we’re really proud of being able to be a stepping stone for them so when they leave our company they go off to a part of the journey that may have not been available to them before. It’s kind of a collaborative thing, we both benefit from it. We both hopefully walk away a bit wiser and a bit smarter from it.