By Sam Bygrave

Romans, wine & bacchanalia

Alcohol has always been able to signify who is part of the elite and who’s not. It used to be back in the ancient day that priests and leaders were the only with access to the booze; that’s the way it was in the early days of the Roman empire anyway. But wine — because that’s what they liked there — slowly became more democratic. The writer Cato thought that even slaves should have access to wine thanks to the medicinal and health benefits of a glass of vino. Most likely though they would have received the lightest, nastiest plonk called lora (it was the leftover grapes and skins and pits that were allowed to ferment and mixed with some spices).

Porter — not just for the working class

Porter has been around for some 300 years — and it takes it name from the working class. But has this working class drink come back around to be a bit of snob’s brew?

In Victorian England, writes the Oxford Companion to beer, it was true that porter was the drink of the working class. It takes its name from the street and river porters of London, who made a living hauling heavy stuff about — sides of pig and barrels of beer and that kind of stuff. After a long day, they liked a bit of this brown beer that had come about. But a class system soon found its way into porter production, as the toffs got wind of the tasty beer.

They liked a version called “robust porter”, according to the Oxford Companion to Beer. It was “considered a beer for connoiseurs, not guzzlers.”

Champagne, not for the feint-walleted

Perhaps at no other time have luxury and privilege come more to a head with the working class than the combustion caused during the French revolution. Marie Antoinette and husband Louis XVI symbolised an old order, and it’s no wonder. When the people were starving they had at their fingertips luxury drops like Veuve Clicquot.

We know this because in 2010 Swedish divers discovered a case of champagne — from the house of Veuve Clicquot — in the midst of a shipwreck. The champagne has been dated to the 1780s, the decade in which revolution swept through France.

It’s believed that King Louis XVI had sent the champagne to the Russian Peter the Great.

Those who have tasted the 230 year old liquid describe it as tasting of tobacco, grapes, white fruits oak and honey.

Bordeaux & rising China

Everyone who has drunk Chateau Lafite raise their hand. That’s right, there’s not many of you. That’s because Lafite is one of Bordeaux first growths, and one of the rarest and most expensive Bordeaux wines going.

But demand for Bordeaux has been on the rise since the China miracle began to happen. China’s rapidly growing number of millionaires (and higher) have taken to acquiring rare and expensive vintages of Bordeaux, driving up auction prices for the stuff. It seems, according to the movie Red Obsession, that the Chinese demand for Bordeaux isn’t about collecting, like it is in the West. In China, they buy the bottles for giving, and pouring at dinner to show their guests their esteem for them.

The World’s Most Expensive Cocktail

Poor Salvatore Calabrese, who’s record for the world’s most expensive cocktail was beaten this year by an Aussie. And we don’t mean poor Sal in a financial sense — have you seen that man’s suits?

We do feel bad that he had some expensive vintage booze that broke before his first attempt. His second attempt, which consisted of a 1788 bottling of Clos de Griffier Vieux Cognac, a 1770 bottling of kummel, an 1860 bottling of orange curacao and some Angostura Bitters from the early 1900s sold for £5,500. That’s pretty money.

But then, here comes the Australians. This year head bartender Joel Heffernan put Crown Casino’s Club 23 in the record books when he put together a cocktail — featuring a cognac from 1858 that costs $6000 a nip — for $12,500. It’s just a shame that the bloke who purchased said expensive drink left it unfinished — but hey, when you’re a baller…

Toffs go to taverns

Alehouse, Inn, Tavern: same-same, right? Well, not according to the English law of 1552 that set up the distinction. There was a strict cap on the number of taverns in every city, with a strict protocol for getting a licence that made it quite difficult, and they ended up being the most exclusive of drinking dens. Clearly they’ve never been to the Terrey Hills Tav. The masses meanwhile were bingeing and brawling out in the alehouses.

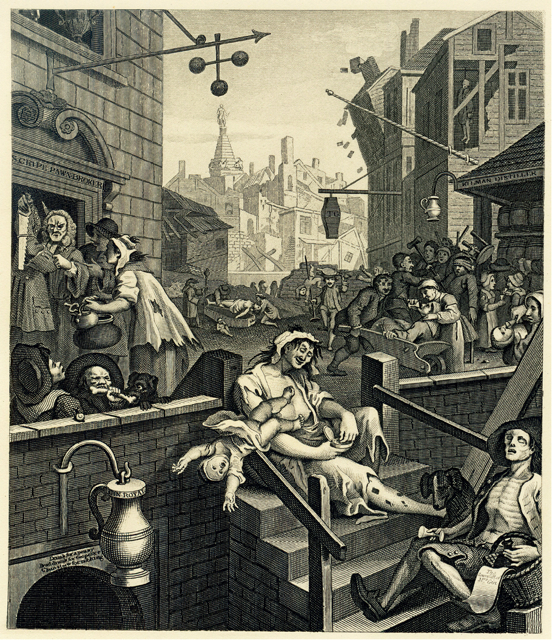

Gin: elixir of the elite, ruin of the rabble

So you knew already that gin lead to a mother’s ruin etc. Gin was a suitable and favourite drink for the English aristocracy: people like Queen Anne to the current Queen have loved a gin here and there. But among the “inferior sort of people” it was decried as having a wicked effect, and “the principal cause of all the vice and debauchery”. Who were the inferior people? Bartenders? Well, yes — some things don’t change!

Punch — the drink that began with the lower class

And that brings us neatly to punch. It has the lowliest of origins, but shows how a little booze, correctly applied, can skip across boundaries of class and becoime a drink of the haves as well as the have-nots. From its earliest origins, on board ships full of syphilitic sailors cruising from port to port without a pot to piss in, it ends up in the Caribbean and gets drunk by those working the sugar plantations.

But it also finds its way into the best households in England and further north in Glasgow, we see the proper preparation of punch becomes a mark of someone’s high station.

Dan Searing’s great book on punch, The Punch Bowl, illustrates how the vessel punch was served in shows the rise of the social ladder it took. Once upon a time, it had been shared from a communal bowl, from whcih everyone literally sipped.But as Searing writes, “as the punch bowl found its way into genteel society, of course, punch drinkers began to sip from glasses.”