In pursuit of grape spirit enlightenment, Tom Bartram journeys to South America

By Tom Bartram

Drink Photography by Steve Brown

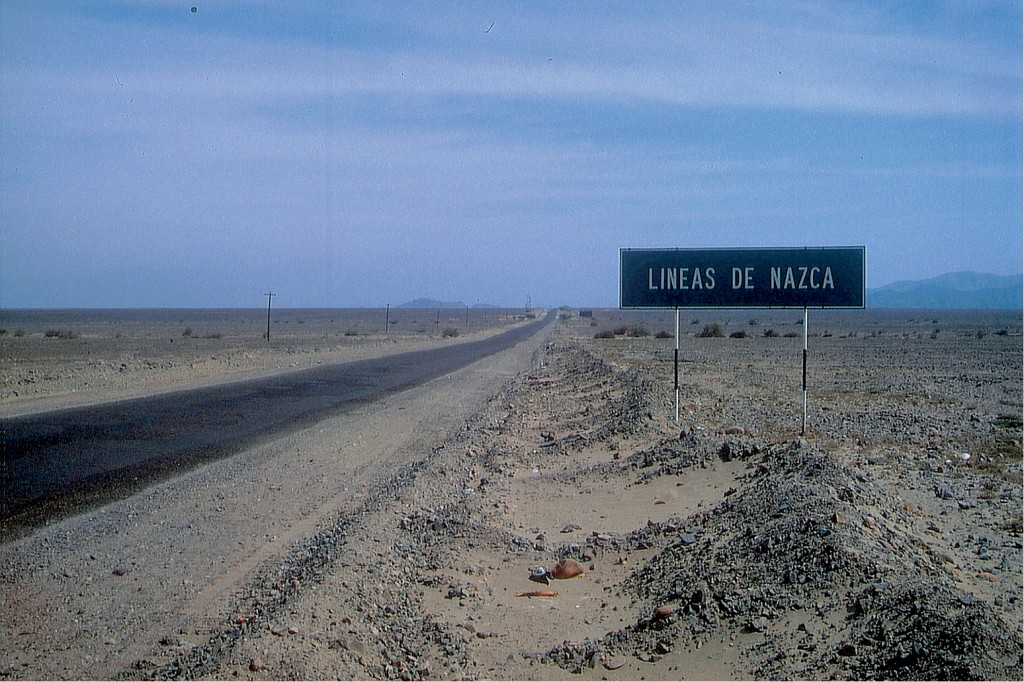

Driving south from Lima towards Ica on the Pan American Highway, it becomes very apparent we’re in the desert. With sand dunes looming, I hear that it almost never rains here. I start thinking perhaps we’d gone the wrong way, until we pass the first of a series of fertile green valleys. These are the valleys where Peruvian pisco is made, 42 of them stretching from the Lima region on Peru’s central coast to Tacna on the southern border with Chile. These little oases are possible due to a series of rivers that carve their way down from high in the Andes, depositing nutrients and minerals with their much needed water.

After 200km we pass the historic port city of Pisco, founded in 1640, from where this great spirit takes its name. Pisco is the native Quechua word for bird, of which there are lots of here attracted by the famously rich sea life. Before the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914, Pisco was a major port of call for sailors on the Cape Horn route around the tip of South America, buying aguardiente de uva (what they used to call pisco) as they made the long and arduous journey around the continent. Although it was produced across the wider region, the spirit became synonymous with its place of purchase (like Panama hats, which actually originate from Ecuador) and in 1825 we have our first written reference to grape spirit being called pisco, by British merchant adventurer William Bennet Stevenson.

Since the powerful 2007 earthquake devastated the city of Pisco is not much to look at, with 80 per cent of buildings said to have been destroyed. You can still see the devastation the 8.0 magnitude quake caused across the region, and rebuilding is slow progress.

The highway curves away from the coast, and ascends into continuing desert. 40km from the ocean, at 400m elevation, 300km south of Lima, the fertile Ica valley comes into view. Ica is pisco’s historical heartland and modern day capital of the industry, where the vast majority of producers can be found. The Ica River gushes through feeding the fertile soils where avocado, pecans, asparagus, and most importantly, grapes grow. By the time of my arrival in late February the harvest season is beginning, turning the valley into a hive of activity.

Ica’s history with grapes most probably stretches further back than anywhere else in South America. Within a few decades of the conquistador’s arrival in Peru in 1532, Spanish settlers noticed the potential of the fertile valley and it soon became the dominant wine region in the new colony. The first evidence of grape spirit production in the Americas also came from here, in the will left by Ica resident Pedro Manuel “the Greek” exactly 400 years ago (1613). Since then it’s been a roller-coaster ride, with high times and more than its fair share of trials and tribulations.

Today the category is booming, but you only have to go back 20 years to find a time when quality pisco was a distant memory of the older generations. Peru was just emerging from its worst few decades in modern history; the brutal dictatorship of Juan Velasco Alvarado in the 1970s, with social upheaval and agrarian land reform killing off almost all Peru’s vines, followed by the violent conflict between the government and the radical Maoist Shining Path revolutionaries throughout the 80s and early 90s. The quality of pisco plunged as quickly as the economy. Poorly produced and adulterated with cane spirit, evidence for this crash in quality can be found in today’s common Pisco Sour spec; lots of citrus and sugar to mask the taste of the foul tasting pisco of those times.

But Peru bounced back from these dark times. Security and market freedom returned in the mid nineties, and paved the way for national pride to kick off not just a renaissance of pisco, but a renaissance of Peru. The gastronomic scene came alive with chefs like Gaston Acurio rediscovering their fantastic culinary heritage and fusing it with modern international cuisine. “Novo-Andino” influenced restaurants can now be found in all the world’s coolest cities. As safety returned the tourists weren’t far behind, and a committed band of pisco producers reemerged, fueling interest in their national spirit and reinstating it as a cornerstone of Peruvian identity. A key moment came in 1999 when Peru finally passed its Denomination of Origin (DOC) with a strict set of rules for pisco production.

In 2004 there were barely 100 brands registered with the DOC. Almost ten years later, that number is over 600. As well as the boom in quality, the quantity has rocketed – only 1.5 million litres were produced in 2002, and that number looks likely to hit 10 million this year. Even so, when you combine this with Chile’s pisco production, it still falls well behind the volumes of its fellow Latin spirits, dwarfed by the volumes of rum, cachaca, and tequila. But with a new generation of passionate producers, some bent on world domination, this category is definitely one you should be paying attention to.

Libations in Lima

Although the gastronomy scene is on fire (the food is amazing!), drinking in Lima can be a bit hit and miss. Pisco Sours are everywhere but finding a good one can prove difficult. Globally the most iconic pisco cocktail, the official national drink must be served by law at every diplomatic function in Peru and her embassies! It is thought to have been invented by American expat Victor Morris, at his Morris’ Bar in Lima shortly after it opened in the mid 1910s. Quebranta Pisco is mixed with egg white, lashings of citrus and sugar, served in a short glass and garnished with a dash or two of bitters.

After Morris died in 1929, the Pisco Sour’s spiritual home moved to the historic bars at the Hotel Maury and the Gran Hotel Bolivar. They became the places to drink and be seen drinking the libation back in the days when they were frequented by the rich and famous. I headed to these bars in search of Pisco Sours at their finest. Above the entrance at the Bolivar it proudly states “La Catedral del Pisco” (The Cathedral of Pisco) but in reality it was far from it. These once iconic classy establishments are tired drab dives, shadows of their former glory serving terrible drinks to tourists.

One exceptional example of a classic Lima hotel bar of this era is The Country Club Lima Hotel in the upmarket suburb of San Isidro. Opened in 1925, this still feels like the play ground of Lima’s elite. I ordered a Capitan, a fantastic mix of equal parts quebranta pisco and sweet vermouth served up and garnished with a cherry. The pecan, raisin and dark chocolate notes from a good Quebranta work perfectly with sweet vermouth, and this sophisticated cocktail fitted perfectly with the timeless classy atmosphere of the bar. The Capitan is thought to have been invented around the time the hotel opened, most probably for Manhattan drinking American expats of which Lima had a large enclave.

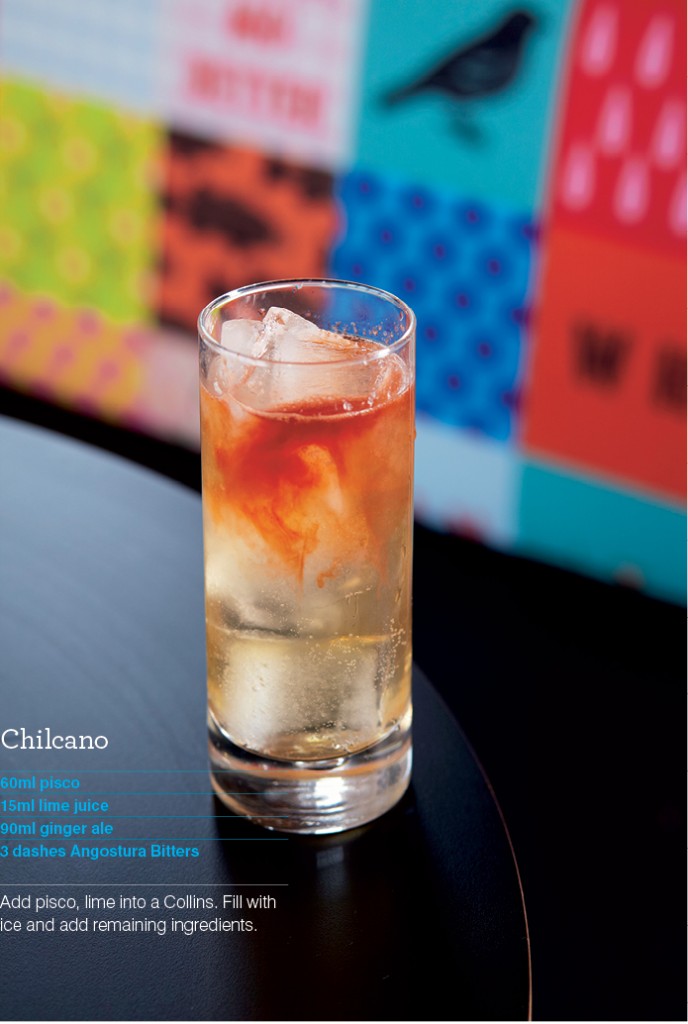

I went on the hunt for more Peruvian classics and didn’t have to look hard to find The Chilcano, a long refreshing drink with pisco, ginger ale, bitters, and lime juice. These are a big hit with Peru’s new generation of younger pisco drinkers, a great thirst quencher in the heat of Lima’s afternoons or the hot atmospheres of the city’s clubs. The Algarrobina is another classic but not quite so popular, and drinking it I realised why. It’s a rich and often sickly concoction of pisco, evaporated milk, a whole egg, sugar, and algarrobina syrup (made from the seeds of the carob tree).

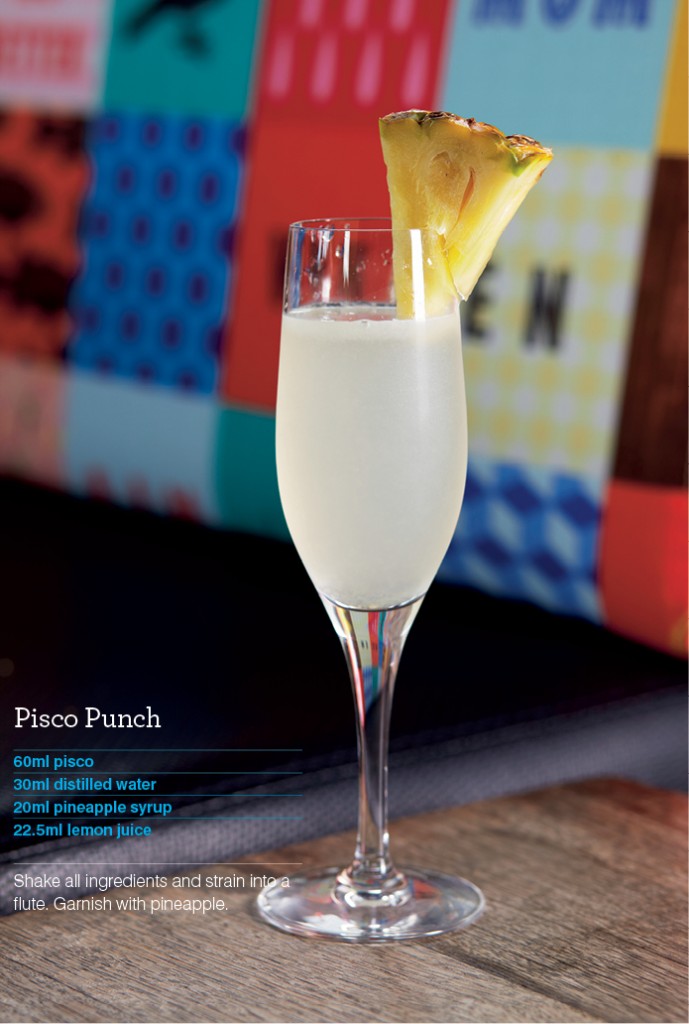

The Pisco Punch is finding its way onto lists around Lima, but it’s not a Peruvian recipe. Although references of Pisco Punch can be found as far back as the 1790s, the recipe that has gained cult status across the world in recent years was invented around the turn of the 20th century by Duncan Nicol, a Scotsman and proprietor of San Francisco’s famous Bank Exchange bar. Although Nicol took the recipe to the grave when he died during prohibition, the recipe used today infuses gomme syrup with pineapple overnight, and mixes it with pisco, lime, and garnished with a piece of the marinated pineapple.

Drinking in Lima is not just about the classic cocktails; there’s a new breed of more experimental cocktail bars in pushing things forward using native herbs and produce from across the country in creative modern cocktails. Drinks are sweet by our standards and based around fruit and citrus, but a good understanding of flavour is clearly demonstrated with some tasty drinks. As Lima’s bartenders are influenced by the ever booming experimental gastronomic scene and exposed to an increasing number of international drinkers, it will be interesting to see how the creative cocktail scene will develop in the coming years.